Summary

Aristotle tackles one of life's most frustrating puzzles: why do we sometimes do things we know are wrong? He distinguishes between different types of moral failure. True vice is when someone genuinely believes bad behavior is good—like a con artist who thinks cheating is smart business. But incontinence (weakness of will) is when you know what's right but can't stick to it—like knowing you should exercise but binge-watching Netflix instead. Aristotle explains this isn't about lacking knowledge but about how emotions can overwhelm our rational thinking, like being drunk or angry. He argues that anger-driven mistakes are more forgivable than appetite-driven ones because anger at least responds to reason (even if it mishears), while pure appetite just wants what it wants. The chapter also explores different types of pleasures, arguing that not all pleasure is bad—some activities are naturally pleasant and good for us. The key insight is that moral failure often happens not because we don't know better, but because our emotions temporarily hijack our decision-making. Understanding this helps us be more realistic about human nature and more strategic about building better habits. Aristotle suggests that people who struggle with self-control aren't necessarily bad people—they're often more redeemable than those who've convinced themselves that wrong is right.

Coming Up in Chapter 8

Having explored the internal battles of self-control, Aristotle turns to examine friendship—the external relationships that shape our character and happiness. He'll reveal why friendship might be more essential to the good life than we typically realize.

Share it with friends

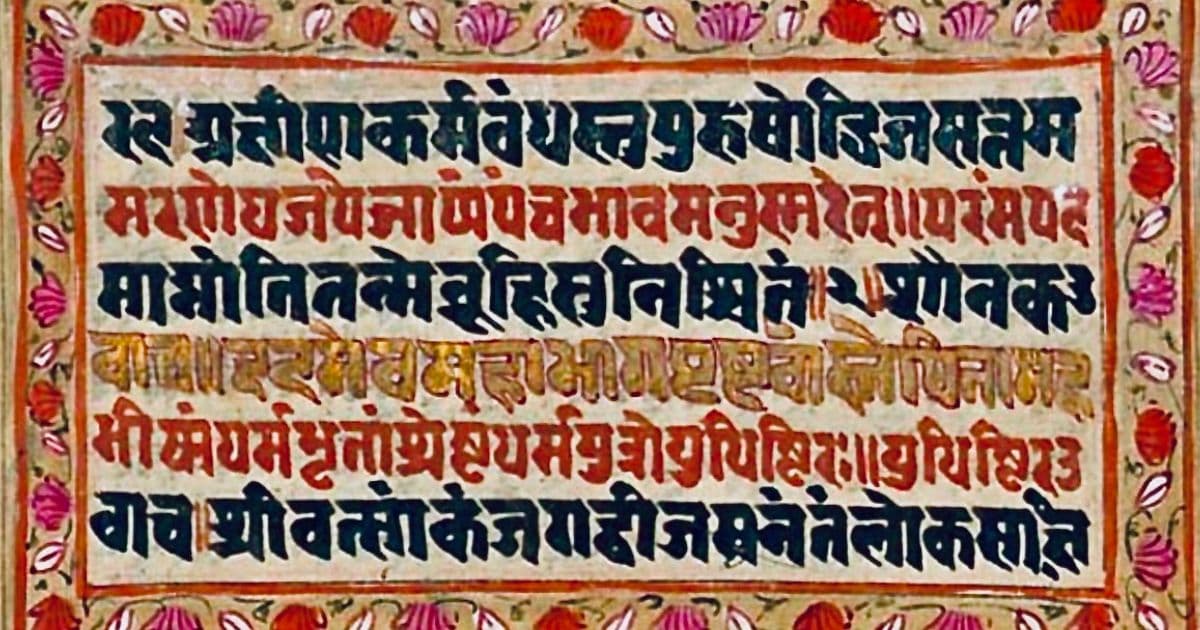

An excerpt from the original text.(~500 words)

OOK VII ====================================================================== 1 Let us now make a fresh beginning and point out that of moral states to be avoided there are three kinds-vice, incontinence, brutishness. The contraries of two of these are evident,-one we call virtue, the other continence; to brutishness it would be most fitting to oppose superhuman virtue, a heroic and divine kind of virtue, as Homer has represented Priam saying of Hector that he was very good, For he seemed not, he, The child of a mortal man, but as one that of God's seed came. Therefore if, as they say, men become gods by excess of virtue, of this kind must evidently be the state opposed to the brutish state; for as a brute has no vice or virtue, so neither has a god; his state is higher than virtue, and that of a brute is a different kind of state from vice. Now, since it is rarely that a godlike man is found-to use the epithet of the Spartans, who when they admire any one highly call him a 'godlike man'-so too the brutish type is rarely found among men; it is found chiefly among barbarians, but some brutish qualities are also produced by disease or deformity; and we also call by this evil name those men who go beyond all ordinary standards by reason of vice. Of this kind of disposition, however, we must later make some mention, while we have discussed vice before we must now discuss incontinence and softness (or effeminacy), and continence and endurance; for we must treat each of the two neither as identical with virtue or wickedness, nor as a different genus. We must, as in all other cases, set the observed facts before us and, after first discussing the difficulties, go on to prove, if possible, the truth of all the common opinions about these affections of the mind, or, failing this, of the greater number and the most authoritative; for if we both refute the objections and leave the common opinions undisturbed, we shall have proved the case sufficiently. Now (1) both continence and endurance are thought to be included among things good and praiseworthy, and both incontinence and soft, ness among things bad and blameworthy; and the same man is thought to be continent and ready to abide by the result of his calculations, or incontinent and ready to abandon them. And (2) the incontinent man, knowing that what he does is bad, does it as a result of passion, while the continent man, knowing that his appetites are bad, refuses on account of his rational principle to follow them (3) The temperate man all men call continent and disposed to endurance, while the continent man some maintain to be always temperate but others do not; and some call the self-indulgent man incontinent and the incontinent man selfindulgent indiscriminately, while others distinguish them. (4) The man of practical wisdom, they sometimes say, cannot be incontinent, while sometimes they say that some who are practically...

Master this chapter. Complete your experience

Purchase the complete book to access all chapters and support classic literature

As an Amazon Associate, we earn a small commission from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and e-book formats

Intelligence Amplifier™ Analysis

The Road of Knowing Better - Why Smart People Make Dumb Choices

When strong emotions temporarily hijack rational decision-making, causing people to act against their own better judgment.

Why This Matters

Connect literature to life

This chapter teaches how to identify when strong emotions are temporarily drowning out your better judgment.

Practice This Today

This week, notice when you make decisions you immediately regret—what emotion was flooding your system right before you acted against your better judgment?

Now let's explore the literary elements.

Terms to Know

Incontinence

Aristotle's term for weakness of will - when you know what's right but can't stick to it. It's different from true vice because the person still knows right from wrong, they just can't control themselves in the moment.

Modern Usage:

We see this every time someone knows they should eat healthy but orders pizza, or knows they should save money but impulse buys online.

Continence

Self-control or the ability to do what you know is right even when you don't feel like it. Aristotle sees this as different from true virtue because it requires struggle - virtuous people naturally want to do good.

Modern Usage:

This is the person who goes to the gym even when they don't want to, or stays patient with difficult customers because it's their job.

Brutishness

Behavior so extreme and savage that it goes beyond normal human vice. Aristotle describes this as almost animal-like cruelty or complete lack of human moral sense.

Modern Usage:

We might see this in extreme criminal behavior or cases of severe mental illness that remove normal moral restraints.

Superhuman virtue

A level of goodness so high it's almost godlike - beyond what we expect from regular humans. Aristotle uses this as the opposite extreme from brutishness.

Modern Usage:

We see this when we talk about saints, or people like Mother Teresa who seem to operate on a different moral level than the rest of us.

Softness

Being unable to endure necessary pain or discomfort, even when you know you should. It's about giving up too easily when things get tough.

Modern Usage:

This shows up when people quit jobs after the first hard day, or avoid difficult conversations they know they need to have.

Practical wisdom

The ability to figure out the right thing to do in specific situations. It's not just knowing rules, but knowing how to apply them wisely in real life.

Modern Usage:

This is what we mean when we say someone has good judgment - they can navigate tricky situations and make decisions that work out well.

Characters in This Chapter

Hector

heroic example

Aristotle uses Homer's portrayal of Hector as an example of someone with superhuman virtue - so good he seems almost divine rather than human.

Modern Equivalent:

The local hero everyone looks up to

Priam

admiring father

Hector's father who recognizes his son's exceptional virtue, saying he seems more like a god's child than a mortal's.

Modern Equivalent:

The proud parent who brags about their accomplished kid

Key Quotes & Analysis

"For he seemed not, he, the child of a mortal man, but as one that of God's seed came"

Context: Priam speaking about his son Hector's exceptional virtue

This quote illustrates Aristotle's concept of superhuman virtue - goodness so exceptional it seems divine. It shows how some people operate on a moral level that amazes even those closest to them.

In Today's Words:

He's so good, he doesn't seem human - more like an angel or something.

"As a brute has no vice or virtue, so neither has a god; his state is higher than virtue"

Context: Aristotle explaining the spectrum from brutish to divine behavior

This reveals Aristotle's view that virtue exists in the human middle ground - we're capable of both terrible and wonderful things. Animals and gods don't struggle with moral choices like we do.

In Today's Words:

Animals can't be evil and gods can't be good - they just are what they are. Morality is a human thing.

"The brutish type is rarely found among men; it is found chiefly among barbarians"

Context: Aristotle describing how rare true brutishness is in civilized society

This shows Aristotle's belief that extreme moral failure is unusual and often linked to circumstances like disease, trauma, or lack of civilization. Most people aren't truly evil.

In Today's Words:

Real monsters are rare - you mostly find that level of awful in really messed up situations.

Thematic Threads

Self-Knowledge

In This Chapter

Understanding the difference between intellectual knowledge and emotional control

Development

Building on earlier discussions of virtue, now examining why virtue is hard to practice

In Your Life:

Recognizing when you're about to make choices you'll regret while you're making them

Human Nature

In This Chapter

Accepting that moral failure often stems from weakness, not wickedness

Development

Deepening the exploration of what makes humans struggle with consistent good behavior

In Your Life:

Being more compassionate with yourself and others when good intentions meet human limitations

Emotional Intelligence

In This Chapter

Learning how different emotions (anger vs. appetite) affect our decision-making differently

Development

Introduced here as a crucial factor in moral behavior

In Your Life:

Noticing which emotions make you most likely to abandon your better judgment

Personal Growth

In This Chapter

Distinguishing between people who can improve and those who've rationalized bad behavior

Development

Evolving from abstract virtue concepts to practical change strategies

In Your Life:

Focusing energy on areas where you struggle with execution rather than understanding

Practical Wisdom

In This Chapter

Building systems that account for emotional reality rather than expecting perfect rational control

Development

Moving from theoretical ethics toward actionable life navigation

In Your Life:

Creating environments and habits that make good choices easier when emotions run high

You now have the context. Time to form your own thoughts.

Discussion Questions

- 1

Aristotle says there's a difference between someone who thinks bad behavior is actually good versus someone who knows what's right but can't stick to it. Can you think of examples of each type from your own experience?

analysis • surface - 2

Why does Aristotle think that emotions can make us act against our better judgment even when we clearly know what we should do? What's actually happening in our minds during these moments?

analysis • medium - 3

Where do you see this pattern of 'knowing better but doing otherwise' showing up most often in modern workplaces, families, or communities?

application • medium - 4

If you were helping someone who struggles with self-control, what practical strategies would you suggest based on Aristotle's insights about how emotions override rational thinking?

application • deep - 5

What does this chapter suggest about how we should judge ourselves and others when we fail to live up to our own standards? How might this change how you approach personal growth?

reflection • deep

Critical Thinking Exercise

Map Your Emotional Override Points

Think about the last three times you did something you knew you shouldn't have done or avoided something you knew you should have done. For each situation, identify what emotion was running high at the time and what your rational mind actually knew was the right choice. Look for patterns in your emotional triggers and the situations where your better judgment gets hijacked.

Consider:

- •Focus on emotions like exhaustion, anger, fear, or stress rather than just 'I was being bad'

- •Notice if certain times of day, situations, or relationships make you more vulnerable to emotional override

- •Consider whether your 'failures' are more like Aristotle's weakness of will or genuine confusion about what's right

Journaling Prompt

Write about one specific emotional trigger that regularly derails your better judgment. What would a realistic system look like to help you navigate this trigger more successfully in the future?

Coming Up Next...

Chapter 8: The Three Types of Friendship

Having explored the internal battles of self-control, Aristotle turns to examine friendship—the external relationships that shape our character and happiness. He'll reveal why friendship might be more essential to the good life than we typically realize.