Summary

Aristotle dissects what makes our actions truly our own versus those we're forced into by circumstances. He explores the gray area between voluntary and involuntary actions—like throwing cargo overboard in a storm to save the ship. While no captain wants to lose goods, the choice to do so in that moment is still voluntary because the principle of action comes from within. This distinction matters because we're only praised or blamed for actions that genuinely originate from us. The chapter then examines choice itself, showing how it differs from mere wish or impulse. We deliberate about means, not ends—a doctor doesn't debate whether to heal, but how to heal. This leads to a crucial insight: virtue and vice are both in our power because we shape our character through repeated actions. Like someone who becomes ill through poor lifestyle choices, we become unjust or self-indulgent through our own repeated behaviors. The chapter concludes with an analysis of courage, revealing it as the mean between cowardice and recklessness. True courage isn't fearlessness—it's facing the right dangers for the right reasons at the right time. Aristotle distinguishes genuine courage from its counterfeits: civic duty, experience, passion, confidence, and ignorance. Each may look brave but lacks the noble motivation that defines true courage.

Coming Up in Chapter 4

Having established the foundation of voluntary action and examined courage, Aristotle will next explore the other virtues that govern our relationships with pleasure, pain, and social interaction—revealing how each virtue represents a careful balance between extremes.

Share it with friends

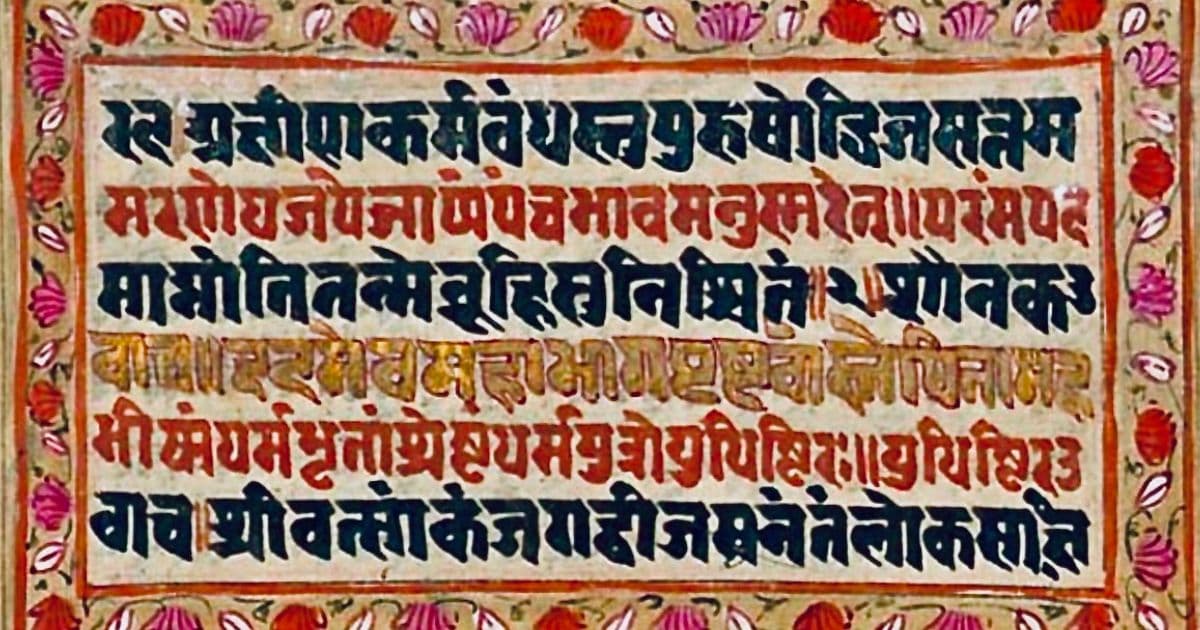

An excerpt from the original text.(~500 words)

OOK III ====================================================================== 1 Since virtue is concerned with passions and actions, and on voluntary passions and actions praise and blame are bestowed, on those that are involuntary pardon, and sometimes also pity, to distinguish the voluntary and the involuntary is presumably necessary for those who are studying the nature of virtue, and useful also for legislators with a view to the assigning both of honours and of punishments. Those things, then, are thought-involuntary, which take place under compulsion or owing to ignorance; and that is compulsory of which the moving principle is outside, being a principle in which nothing is contributed by the person who is acting or is feeling the passion, e.g. if he were to be carried somewhere by a wind, or by men who had him in their power. But with regard to the things that are done from fear of greater evils or for some noble object (e.g. if a tyrant were to order one to do something base, having one's parents and children in his power, and if one did the action they were to be saved, but otherwise would be put to death), it may be debated whether such actions are involuntary or voluntary. Something of the sort happens also with regard to the throwing of goods overboard in a storm; for in the abstract no one throws goods away voluntarily, but on condition of its securing the safety of himself and his crew any sensible man does so. Such actions, then, are mixed, but are more like voluntary actions; for they are worthy of choice at the time when they are done, and the end of an action is relative to the occasion. Both the terms, then, 'voluntary' and 'involuntary', must be used with reference to the moment of action. Now the man acts voluntarily; for the principle that moves the instrumental parts of the body in such actions is in him, and the things of which the moving principle is in a man himself are in his power to do or not to do. Such actions, therefore, are voluntary, but in the abstract perhaps involuntary; for no one would choose any such act in itself. For such actions men are sometimes even praised, when they endure something base or painful in return for great and noble objects gained; in the opposite case they are blamed, since to endure the greatest indignities for no noble end or for a trifling end is the mark of an inferior person. On some actions praise indeed is not bestowed, but pardon is, when one does what he ought not under pressure which overstrains human nature and which no one could withstand. But some acts, perhaps, we cannot be forced to do, but ought rather to face death after the most fearful sufferings; for the things that 'forced' Euripides Alcmaeon to slay his mother seem absurd. It is difficult sometimes to determine what should be chosen at what cost, and what should be endured in return...

Master this chapter. Complete your experience

Purchase the complete book to access all chapters and support classic literature

As an Amazon Associate, we earn a small commission from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and e-book formats

Intelligence Amplifier™ Analysis

The Road of True Ownership - When Your Actions Are Actually Yours

The ability to distinguish between actions forced by circumstances and those genuinely chosen, taking full responsibility only for what truly originates from within.

Why This Matters

Connect literature to life

This chapter teaches how to identify which parts of difficult situations you actually control versus which parts are imposed by external forces.

Practice This Today

This week, when facing pressure at work or home, pause and ask: 'What part of this situation is genuinely mine to choose?' Own your response completely, but don't take responsibility for circumstances beyond your control.

Now let's explore the literary elements.

Terms to Know

Voluntary vs. Involuntary Action

Aristotle's distinction between actions that truly come from within us versus those forced by outside circumstances. The key is whether the moving principle comes from the person acting or from external compulsion.

Modern Usage:

We use this when deciding accountability - like whether someone who commits a crime under threat should be punished the same as someone who chose freely.

Deliberation

The process of thinking through how to achieve something we want. Aristotle says we don't deliberate about our goals, but about the means to reach them.

Modern Usage:

This is what we do when we know we want a promotion but figure out whether to work overtime, take classes, or network to get it.

The Doctrine of the Mean

Aristotle's idea that virtue lies between extremes - courage sits between cowardice and recklessness. Most virtues are about finding the right balance.

Modern Usage:

We see this in advice like 'be confident but not arrogant' or 'be generous but don't let people take advantage of you.'

Choice (Prohairesis)

Different from wish or impulse, choice involves deliberation about what's in our power. It's the result of thinking through our options and deciding.

Modern Usage:

This is the difference between wanting to eat healthy and actually choosing the salad over the burger after thinking about your goals.

Civic Courage

Acting brave because of social pressure, duty, or fear of punishment rather than from genuine virtue. Looks like real courage but lacks the right motivation.

Modern Usage:

Like a soldier who fights well only because he's afraid of court martial, or someone who speaks up at work only because HR requires it.

Moral Responsibility

The idea that we're accountable for our character because we shape it through repeated actions. We become what we repeatedly do.

Modern Usage:

This applies when we realize our bad habits aren't just things that happen to us - we created them through our choices over time.

Characters in This Chapter

The Ship Captain

Example figure

Represents someone making a voluntary choice under pressure. Throws cargo overboard in a storm - loses goods but saves lives through deliberate action.

Modern Equivalent:

The manager who has to lay off staff to save the company

The Person Under Tyranny

Moral dilemma example

Forced to choose between doing something wrong or watching family die. Shows the complexity of voluntary action when all options are terrible.

Modern Equivalent:

The parent who lies to protect their child from serious consequences

The Coward

Negative example

Someone who feels fear about the wrong things, at the wrong time, or in the wrong way. Represents the deficiency of courage.

Modern Equivalent:

The person who won't speak up about workplace problems even when it really matters

The Reckless Person

Negative example

Someone who doesn't feel appropriate fear and rushes into danger without good reason. Represents the excess of courage.

Modern Equivalent:

The person who always picks fights or takes unnecessary risks to prove they're tough

Key Quotes & Analysis

"Such actions, then, are mixed, but are more like voluntary actions; for they are worthy of choice at the time when they are done."

Context: Discussing actions like throwing cargo overboard in storms

This shows that even under pressure, we can still make genuine choices. The circumstances are terrible, but the decision still comes from within us based on what we think is best in that moment.

In Today's Words:

Yeah, it's a bad situation, but you still chose what to do - and that choice says something about who you are.

"We deliberate not about ends but about means."

Context: Explaining how human decision-making actually works

This reveals that our goals usually aren't up for debate - a doctor wants to heal, a parent wants to protect their child. The real thinking happens when we figure out how to achieve what we want.

In Today's Words:

You don't sit around wondering if you want to be happy - you figure out what will actually make you happy.

"It was in our power not to become unjust."

Context: Arguing that we're responsible for our own character

This is Aristotle's tough love moment. He's saying we can't blame our bad character on circumstances because we shaped it through thousands of small choices over time.

In Today's Words:

You didn't end up this way by accident - you made choices that got you here.

Thematic Threads

Personal Agency

In This Chapter

Aristotle distinguishes voluntary from involuntary actions, showing how true choice requires internal origin and knowledge of circumstances

Development

Builds on earlier discussions of virtue by examining when we're truly responsible for character development

In Your Life:

You might recognize this when deciding whether to blame yourself for outcomes beyond your control versus owning your actual choices.

Character Formation

In This Chapter

Repeated actions shape who we become—we create our own virtues and vices through habitual choices

Development

Deepens the earlier theme that virtue is learned behavior by showing how we actively construct our character

In Your Life:

You see this in how your daily responses to stress or conflict gradually shape your reputation and self-image.

Social Expectations

In This Chapter

Different forms of courage are valued differently—civic duty versus true moral courage have distinct social rewards

Development

Introduced here as analysis of what society calls 'courage' versus genuine virtue

In Your Life:

You might notice this when workplace 'team players' get promoted while those with genuine principles face resistance.

Practical Wisdom

In This Chapter

Deliberation focuses on means, not ends—we figure out how to achieve what we already value

Development

Extends earlier themes about rational decision-making by showing the proper scope of deliberation

In Your Life:

You apply this when you know you want better health but need to figure out which specific changes will work for your lifestyle.

Authentic Motivation

In This Chapter

True courage requires noble motivation, not just brave-looking behavior driven by duty, experience, or ignorance

Development

Introduced here through analysis of genuine versus counterfeit virtue

In Your Life:

You might recognize this when questioning whether you're helping others from genuine care or just to look good.

You now have the context. Time to form your own thoughts.

Discussion Questions

- 1

When Aristotle talks about throwing cargo overboard in a storm, what makes this action voluntary even though no captain wants to lose their goods?

analysis • surface - 2

Why does Aristotle say we can only be praised or blamed for actions that truly originate from within us? What's the difference between reacting and choosing?

analysis • medium - 3

Think about a recent conflict at work or home. Which parts of your response were genuine choices versus reactions to circumstances beyond your control?

application • medium - 4

Aristotle argues that we shape our character through repeated actions, like how someone becomes ill through poor lifestyle choices. How would you apply this to building better habits in your own life?

application • deep - 5

What does Aristotle's analysis of courage versus its counterfeits teach us about the difference between looking virtuous and actually being virtuous?

reflection • deep

Critical Thinking Exercise

Map Your Choice Points

Think of a recent stressful situation where you felt like you had no options. Draw a simple timeline of what happened. Above the line, mark the external pressures and circumstances you couldn't control. Below the line, mark every moment where you had a genuine choice about your response, words, or actions. Be honest about which consequences you truly own.

Consider:

- •External pressures often feel like they eliminate choice, but they rarely eliminate all choice

- •Your genuine choices might be small (tone of voice, body language) but they're still yours to own

- •The goal isn't to blame yourself, but to identify where your real power lies

Journaling Prompt

Write about a pattern you notice in how you respond to pressure. What would it look like to take full ownership of your genuine choices while releasing responsibility for circumstances beyond your control?

Coming Up Next...

Chapter 4: Money, Honor, and Finding Your Balance

Having established the foundation of voluntary action and examined courage, Aristotle will next explore the other virtues that govern our relationships with pleasure, pain, and social interaction—revealing how each virtue represents a careful balance between extremes.